|

..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... ..... .....

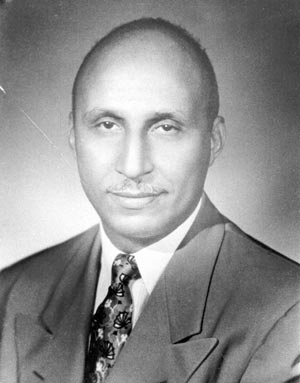

Bro. Hill was an instrumental member of an NAACP-affiliated legal team that persistently attacked segregation. He also was a lead lawyer on a Virginia case later incorporated into Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 case in which the U.S. Supreme Court declared segregated schools unlawful.

He lacked the renown of his Howard University Law School classmate Thurgood Marshall, who later became a Supreme Court justice, but at one time, Hill had 75 civil rights cases pending. He is estimated to have won $50 million in better pay and infrastructure needs for the state's black teachers and students during his career.

Bro. Hill, who was raised in Washington and graduated from Dunbar High School, spent his public life in Richmond, where he first won widespread attention in 1948 as the first black person elected to the City Council in 50 years. Although his term in office was short, his civil rights legacy proved far more enduring because of his role as a lead lawyer in Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Va., one of the five cases the U.S. Supreme Court combined into its landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling. Marshall was the lead lawyer in the high court case.

Hill's involvement in the Davis case began through his affiliation with the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and he worked closely with a team that included Marshall; Howard Law School Dean Charles Hamilton Houston, who had been a mentor to Marshall and Hill; and Spottswood W. Robinson III, a future Howard law dean and chief judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit.

Their goal was to challenge more than the existing "separate but equal" system of public facilities that had been created with the U.S. Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson.

In 1951, Hill and Robinson took up the cause of students at an all-black high school in Farmville, Va., who had gone on a two-week strike to protest the leaky roof and other substandard conditions of the tar-paper building. This became the Davis case.

During and after the Brown decision, Hill remained an instrumental force in developing legal strategies during Virginia's "massive resistance" to desegregation, in which many public schools closed rather than admit blacks.

He filed countless suits in the state to compel change in such areas as voting rights, jury selection, access to school buses and employment protection.

Hill's activism came at a price. A cross was burned on his lawn in 1955, and his family received so many threats that his wife installed floodlights.

At the time, Hill said officials in Richmond "had the ambulance, the fire department and the undertaker all sent to my house in about 15 minutes of each other" to intimidate him.

He told the publication Human Rights in 1994: "I can't understand why Americans are willing to send their children -- black and white -- to foreign lands to fight, and sometimes die, to preserve the American concepts of freedom, democracy and civil rights, when at the same time these same Americans are unwilling to undergo an occasional inconvenience or suffer a slight financial loss to help break down racial barriers and racial discrimination in this country."

He was born Oliver White in Richmond on May 1, 1907. After his parents divorced, he took the surname of his stepfather. The family settled in Washington D.C., where, as Oliver Hill, he graduated from Dunbar High School.

Law became his chief interest after an uncle died and left him a copy of the Constitution. He said he saw himself as an activist early on and was determined to "correct the mistake made in 1896," meaning the Plessy v. Ferguson ruling.

Hill was a 1931 graduate of Howard University and a 1933 graduate of its law school, where he finished second to Marshall in class rank. While at Howard, Bro. Hill pledged Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Alpha Chapter in the Spring of 1927.

It took many years for Hill to establish himself. An early law practice in Roanoke went under during the Depression, and he waited tables in Washington until opening a law office in Richmond in 1939.

One of his early victories was an equal-pay case involving black teachers in Norfolk. Hill also worked on segregation matters including voting rights and redlining, a discriminatory mortgage-lending practice.

After returning from Army service during World War II, Hill unsuccessfully ran as a Democrat in 1947 for a seat in the Virginia House of Delegates. His effort received national attention because, if he had won, he would have been the first black person in the General Assembly since 1889.

The next year, he won a seat on the Richmond City Council, the first African American elected on the City Council since Reconstruction, in large part because of a concerted effort by the city's black community to support him.

He lasted a term before losing reelection -- a loss attributed to different voting patterns in the black community. He was briefly considered a contender to replace a council member who resigned, but he was rejected by other members of the all-white council.

Hill sat on the national Democratic Party's Biracial Committee on Civil Rights in 1960, and the next year President John F. Kennedy named him to the Federal Housing Administration as an assistant to commissioner. During his five-year stint, Hill oversaw racial fairness policies in housing.

Afterward, he returned to his Richmond practice, whose partners included Henry L. Marsh III, who became the city's first black mayor and is now a Democratic state senator.

Hill continued to work until he went blind in the late 1990s and shortly afterward published a memoir, "The Big Bang: Brown v. Board of Education and Beyond."

During his career, Hill won many awards from black legal and civic groups. In 1994, he received high honors from the American Bar Association and the NAACP. In 1999, President Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the nation's highest civilian honor.

Among the Richmond buildings named for Hill is one he visited as a young lawyer because it housed the state Supreme Court of Appeals and a law library.

At a 2005 dedication, he was too frail to speak, but a family member read his statement: "Who would have thought back in 1939, given the racial climate at the time, that 66 years later that building would be named after me."

Awards & Honors

Bro. Hill's accomplishments have earned many awards and citations including the 1959 "Lawyer of the Year Award" from the National Bar Association, the "Simple Justice Award" from the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund in 1986 and the American Bar Association "Justice Thurgood Marshall Award" in 1993. President Bill Clinton awarded Bro. Hill the "Presidential Medal of Freedom" in 1999. Students at the University of Virginia also honored Hill when they founded the Oliver W. Hill Black Pre-Law Association.

In 2000, he received the American Bar Association Medal, and the National Bar Association "Hero of the Law" award. In September 2000, he and other NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyers were honored with the "Harvard Medal of Freedom" for their role in the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision. In 2005 he was awarded the Spingarn Medal, the NAACP's highest honor. He's also a renowned member of Omega Psi Phi Fraternity, Inc. receiving the award of National Omega Man of the Year in 1957.

In Richmond, a bronze bust of him is visible at the Black History Museum and Cultural Center of Virginia. The city's Oliver Hill Courts Building was named for him.

In October 2005, Virginia Governor Mark R. Warner dedicated a newly renovated building in Virginia's Capitol Square in his honor. The Oliver W. Hill Building is the first state-owned building as well as the first in Virginia's Capitol Square to be named for an African American. "Oliver W. Hill has worked tirelessly to end the injustice of segregation, and today we honor his lifetime of contributions to our commonwealth and our nation" said Governor Warner. "It's my hope that the generations of Virginians and Americans who come after us and visit this Square will think that the history we reflect in our monuments is as rich and diverse as our people, and that the heroes that this generation has chosen to honor bring new and vital lessons."

Oliver Hill's autobiography: The Big Bang: Brown v. Board of Education, The Autobiography of Oliver W. Hill, Sr. edited by Professor Jonathan K. Stubbs, was published in 2000.

On Sunday, August 5, 2007, Oliver Hill died peacefully during breakfast at his home in Richmond, Virginia of natural causes at the age of 100 years old. Later that day, Virginia Governor Tim Kaine issued a statement, saying:

"As a pioneer for civil rights, an accomplished attorney, and a war veteran, Mr. Hill's dedication to serving the Commonwealth and the country never failed. And, despite all of the accolades and honors he received, Mr. Hill always believed his true legacy was working to challenge the conscience of our Commonwealth and our country."

Source: www.statemaster.com, www.washingtonpost.com

Click here to watch an inspiring interview of Bro. Hill

|